In a

previous post I showed how a grid based on projecting a gridded cube onto a sphere could improve on a lat/lon grid, with a much less extreme singularity, and sensible neighbor relations between cells, which I could use for diffusion infilling. Victor Venema suggested that an icosahedron would be better. That is because when you project a face onto the sphere, element distortion gets worse away from the center, and icosahedron faces projected have 2/5 the area of cubes.

I have been revising my thinking and coding to have enough generality to make icosahedrons easy. But I also thought of a way to fix most of the distortion in a cube mapping. But first I'll just review why we want that uniformity.

Grid criteria

The main reason why uniformity is good is that the error in integrating is determined by the largest cells. So with size variation, you need more cells in total. This becomes more significant with using a grid for integration of scattered points, because we expect that there is an optimum size. Too big and you have to worry about sample distribution within a cell; too small and there are too many empty cells. Even though I'm not sure where the optimum is, it's clear that you need reasonable uniformity to implement such an optimum.

I wrote

a while ago about tesselation that created equal area cells, but did not have the grid aspect of each cell exactly adjoining four others. This is not so useful for my diffusion infill, where I need to recognise neighbors. That also creates sensitivity to uniformity, since stepping forward (in diffusion) should spread over equal distances.

Optimised grid

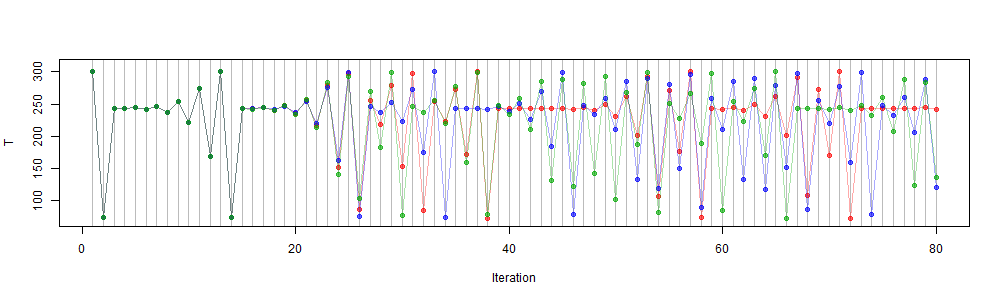

I'll jump ahead at this stage to show the new grid. I'll explain below the fold how it is derived and of course, there will be a WebGL display. Both grids are based on a similarly placed cube. The left is the direct projection; you can see better detail in the

previous post. Top row is just the geometry (16x16), the bottom shows the effect of varying data (as before 24x24, April 2015 TempLS). I've kept the coloring convention of s different checkerboard on each face, with drab colors for empty cells, and white lines showing neighbor connections that re-weight for empty cells.

The right is the same with the new mapping. You can see that near the cube corner, SW, in the left pic the cells get small, and a lot become empty. IOn the right, the corner cells actually have larger area than in the face centre, and there is a minimum size in between. Area is between +-15% of the center value. In the old grid, corner cells were about 20% area relative to central. So there are no longer a lot of empty cells near the corner. Instead, there are a few more in the interior (where cell size is minimum).

In that previous post, I showed a table of discrepancies in integrating a set of spherical harmonics over the irregularly distributed stations:

| L | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5

|

| Full grid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1e-06

|

| Infilled grid | 8.8e-05 | 0.00029 | 0.001045 | 0.002015 | 0.003635

|

| No infill | 0.007632 | 0.027335 | 0.049327 | 0.064493 | 0.075291

|

In the new grid, the corresponding results are:

| L | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5

|

| Full grid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1e-06

|

| Infilled grid | 8e-06 | 0.00019 | 0.000645 | 0.001348 | 0.002529

|

| No infill | 0.004758 | 0.02558 | 0.047794 | 0.0601 | 0.069348

|

Simply integrating the SH on the grid (top row) works very well in either. Just omitting the empty cells (bottom row), the new grid gives a modest improvement. But for the case of interest, with the infilling scheme, the result is considerably better than with the old grid.

Optimising

I think of two spaces - z, the actual sphere where the grid ends up, and u, the grid on each cube face. But in fact u can be thought of abstractly. We just need 6 rectangular grids for u, and a mapping from u to z.

But the mapping need not be simple projection. You could, for example, re-map the u space and then project. If f is a one-one mapping of the square of u onto itself, then the change in area going to z is:

det(f'(u))/(1+f

2(u))^(3/2)

where the second factor comes from the projection, and includes the inverse square magnification and a cos term for the different angles of the du element and the sphere. f' is a Jacobian derivative on the 2D space, and the determinant gives the area ratio of that u mapping.

I use the mapping f(u)=1/r tan(r*u) on each parameter separately. The actual form of f doesn't matter very much. I choose tan because if tan(1/r)=sqrt(2) it gives the tesselation of great circles separated by equal longitude angle. That is already much better than simple projection (r=0). I can check by calculating what would happen to a square in the centre, mid-side, and corner, for various r:

| | | | | |

|

| 1/tan(1/r) | 0 | 0.7071 | 1 | 1.1312 | 1.2

|

| central | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1

|

| midside | 0.3536 | 0.5303 | 0.7071 | 0.8059 | 0.8627

|

| corner | 0.1925 | 0.433 | 0.7698 | 1 | 1.1458

|

The top row actually shows a slightly modified r; and the bottom two show ratios of area to the central area. For small r it is small, so areas vary by about 5:1. For the case of great circle slicing, it is about 2:1, and for larger r it gets better. I've chosen tan(1/r)=5/6.

hat means the midside areas are down by about 15%, and so most of the area is within that range. At the corners, a small section, it rises to +15%. There is associated distortion, so I don't think it is worth pushing r higher. That would improve average uniformity, but the ends would then be both large and distorted.

So here finally is the 24x24 WebGL plot equivalent to that from last time. Again it shows with drab colors empty cells, and with white lines the direction of reallocation of weights for infill. The resulting improved integration is discussed in the head plot.